While the short term ramifications of the Brexit vote on 23 June are still working themselves out, the likely long term economic and investment impact is arguably clearer.

Economic implications

Many prominent economists appear to agree that Brexit need not have a long-lasting detrimental affect on the UK economy.

Official trade statistics show that the European Union (EU) is the destination for about half of all British exports. Specifically, about 44% of UK exports in goods and services went to the EU in 2015 (£220 billion out of £510 billion total exports).

However, the UK also forms an important export market for Europe so there are commercial advantages for both sides in continuing a close commercial arrangement.

Moreover, economist Professor Steve Keen argues that leaving Europe won’t result in sky-high barriers to economic trade as overt discrimination would breach World Trade Organisation rules. He believes the UK is unlikely to end up with a deal much worse than that of the USA with Europe, where the average tariff is 2%.

This average disguises differences across a variety of products, where some products have no tariff (laptops), some have a 10% tariff (cars) and a few have a 30% tariff (clothing). Thus, the impact upon specific industries will naturally vary.

Given that most of world demand is generated outside of Europe, and the UK’s trade with other areas has been growing at a faster pace, Brexit could actually help British exports in the long run if the UK is able to negotiate favourable terms with these areas.

Certainly, it is difficult to disagree with the assessment of macro economic consultancy Capital Economics, in a report examining the long-term economic implications of Brexit, when it states: “Although the impact of Brexit on the British economy is uncertain, we doubt that Britain’s long-term economic outlook hinges on it.”

In the long term, foreign inward investment into the UK need not suffer unduly as access into the single market is not the sole reason firms invest here. Being the fifth or sixth largest global economy (depending on the strength of sterling) is sufficient reason for overseas investors to invest, while ease of doing business here with the legal and financial expertise available may be further encouraged by tax incentives.

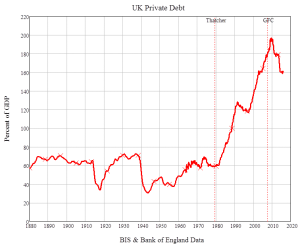

There are some concerns that the financial services sector may shrink slightly in the long term. While Professor Keen believes such fears are overblown, such an outcome might be no bad thing if it forces the UK to successfully rebalance an economy that has relied too heavily on credit creation and increasing private debt to fuel consumption-led growth.

He argues that it was an inevitable slowdown in the growth of private debt (see chart) that led to the ‘Great Financial Crisis’ (GFC), and considers that an unsustainable level of private debt, “is the main threat to the UK’s economic prosperity, not Brexit”.

Again, Capital Economics is similarly sanguine in its assessment of the long term impact of Brexit:

“Things have changed a lot since 1973, when joining the European Economic Community was a big deal for the United Kingdom. There are arguably much more important issues now, such as whether productivity will recover. The shortfall in British productivity relative to its pre-crisis trend is still over 10%, so regaining that lost ground would offset even the most negative of estimates of Brexit on the economy.”

The panicked reaction of many will produce outstanding opportunities for patient investors with cool heads prepared to take a longer view.

As Warren Buffett famously quipped, “Price is what you pay, value is what you get”, and it’s a maxim to be borne in mind before investing in any asset. It’s vital to conduct thorough research, evaluating the risks before investing, while working to a sensible timeframe. Rushing in or out of investments driven purely by greed or fear in increasingly volatile markets is a sure recipe for serious errors.

Long term investors (in contrast to traders adopting a short term view) can be confident that the normal investing rules still apply post-Brexit. Indeed, careful portfolio construction matters in all market environments, especially during periods of increasing volatility. This is because an over reliance on any single asset class introduces the risk that investors may miss out on potentially attractive returns and increases the risk of losses.

European impact

The long term impact of Brexit upon the European Union may be profound if it leads to the eventual break-up of the European Union itself.

Given the economic problems and high unemployment levels faced by the citizens of Greece, Spain, Portugal, France and Italy a successful Brexit is likely to encourage similar moves by an electorate already disillusioned with failed EU economic policies.

A one-size fits all monetary policy for countries within the Eurozone, alongside a policy of austerity, appears to have benefited Germany at the expense of its economically weaker European partners. It’s quite likely that some of the disillusioned countries will eventually follow the UK lead, leaving a ‘core’ Europe centred around Germany.

That said, such moves might in the longer term lead to faster rates of growth for those countries leaving. For example, it is difficult to argue that the Greek economy could be any worse off if it were to quit the euro and leave the EU.

Such changes naturally present risks and opportunities for long term investors, and again a diversified portfolio seeking out quality assets with a long term horizon would be key to reducing risk while seeking to maximise the benefits of a sound investment policy.

Global perspective

While news of Brexit did unsettle global financial markets, it will probably have a negligible long-term economic impact at a global level. After all, the UK gross domestic product represents only around 2.35% of the global total, according to the Institute of Economic Affairs.

In that respect long term investors can look forward to a continuing world of opportunity.